Humankind is a very precarious and complex thing- humans are volatile and intense, yet also fragile and impressionable. We are very different from the other creatures that roam this planet with us, yet there is also a kinship we share with them as fellow inhabitants of our earth. One such creature, a humble homo sapien by the name of Gary Larson, giving a great deal of thought into these domains of existence, with constant ponderance as to how they intertwine and interact with one another, found that his favorite way to portray them was through a little something called laughter. Humor, he found, was key in the way one looks at the world, which he brings to life through his artistry and thus, the graphic witnessing of the human species.

So, who is Gary Larson? First and foremost, he is a nerd (self-identified), a human, comic, cartoonist, comic-cartoonist, etc. While Gary did not grow up wanting to be a cartoonist, drawing was always an art form close to his heart. In his youth, he took up employment in a music store and in his boredom there, began sketching panels, which he then was able to sell to a local magazine, then others to the Seattle Times, and later receiving a (very lucky) syndication deal through the San Francisco Chronicle (which is a truly exhilarating story in itself). From there, he became a regular cartoon panelist of The Far Side, which ran with the San Francisco Chronicle and Universal Press Syndicate for 15 years from 1980 to 1995. The Far Side panels were later compiled and published into 23 books, all of which were on the New York Times Bestseller List. The single-panel comics were first collected into smaller books, and a selected collection was then republished into these larger, best-of collections, notably The Far Side Galleries. The books and ‘galleries’ were, and remain, immensely popular, with celebrity fans like Stephen Jay Gould, Stephen King, Robin Williams, Steve Martin, and Jane Goodall (more on her later) penning forewords for them. There were also two animated specials, both produced by Gary, titled Tales from the Far Side that were released in 1994 and 1997, respectively. His work was also exhibited in the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C., which later became a traveling exhibit and toured all throughout the country. Also notably, the California Academy of Science featured his panels and included a giant microscope under which visitors could stand and look up to see a giant eyeball, one of the gags from Gary’s cartoons (California).

Markedly, however, even with the popularity he has now, Gary never wanted to be famous. Even with the success that The Far Side comics have enjoyed, he has what one reporter describes as the “Larson yin-yang combination of a slight ego and a massive self-awareness, in which he doesn’t need to be idolized, but he doesn’t want to be thought of as lame” (Stein/Seattle). In short, Gary is simply a normal guy. A normal, relatable, and hilarious man. My own personal experience with Gary has been very good, and reading his comics was something of a staple during my childhood and adolescence. It was actually these very Far Side galleries that were some of my first experiences in the graphic world, excluding the Sunday Funnies in the morning newspaper. It was my mother who introduced me to The Far Side, as she also had been an avid fan ever since she discovered them when she was in middle school. She actually credits his published works, along with the classic King of the Hill as the things that got her through grad school. Gary’s cartoons were also a bit of a catalyst in my own life for my understanding of some more adult humor, as I am still only now understanding certain jokes for the first time while rereading panels I originally read when I was 14. This sort of new world that Gary’s panels were opening up for me is another reason his books were so impactful on me and my own journey as a writer. This is because The Far Side cartoons were the first to show me how to create a story with only a few words, or even no words at all, and how even that could be something very meaningful and powerful to a reader. And as someone who, as a child, wanted to be both an artist (sketching/drawing) and a writer, it was a wild concept to be able to do both at the same time. I quickly became entranced with The Far Side, relishing the distinct Larson-morbidness and refreshingly dark humor and zestiness it added to my life.

There is another thing to say about Gary’s iconic artistic style, featuring surrealistic humor, often based off of awkward social situations (relatable, no?), far-fetched circumstances, logical fallacies, bizarre occurrences, an anthropomorphic worldview, and the classic search for the meaning of life. In The Prehistory of The Far Side: A 10th Anniversary Edition, Gary reveals that the question he’s most often confronted with is where his ideas for his comics come from (with “Why do you get your ideas?” following as a close second), and he responds with a joke about rummaging through his grandparents’ attic and discovering a large, fancy book entitled Five Thousand and One Weird Cartoon Ideas, before admitting he just doesn’t know. He does, however, concede that caffeine is generally a key ingredient to get his creative juices flowing and that his ideas for cartoons are rarely spontaneous. He also includes what he says is the only cartoon idea that stems directly from his own personal experience, which is a single, wordless panel depicting a newly-installed chin-up bar in a doorway that has been impressively dented and on the floor, the legs and feet and a fallen man, surrounded by a cluttering of broken wood and a wonky pair of broken glasses (41).

Gary’s comics also contain what is described by another reporter as “pothead-meets-scientist”, and rightfully so (Stein/Seattle). His works definitely have a major vibe of someone who is just living life a little bit buzzed, which makes it all the more memorable. The other very distinct quality of Gary’s work is that they are largely influenced by his background in science. He was actually a biology major in college and had plans to be an entomologist (Mancini). Gary has stated that his first love was science and according to him, “specifically, when placed in a common jar, which of two organisms would devour the other” (13). This fascination with science is evident in his works, with the chapters in his books being titled things like ‘Origin of Species’, ‘Evolution’, ‘Mutations’, ‘Stimulus-Response’, and ‘The Exhibit’ and many of his panels showing clear influence from not just sociological and anthropological views, but also biological. Fun Fact: Gary, though not technically a scientist, is very well-known and lauded in the professional science community, with a species of louse, beetle, and butterfly each being named in his honor (Strigiphilus garylarsoni, Garylarsonus, and Serratoterga larsoni, respectively).

Though Gary’s work was quite popular upon publication, and still is today, not all were as entranced as I with his art. Some of Gary’s work, though it may seem tame by today’s standards, was actually quite racy at the time of publication. Many Larson critics describe his humor as ‘sick’, something which he agrees with and says he got from his own family’s “morbid” sense of humor, and that he was heavily influenced by his older brother Dan’s “paranoid” sense of humor (Weise & The Mag). In the foreword to his 10th Anniversary ‘exhibit’ of The Far Side, he warns readers that if “your refrigerator is currently covered with Family Circus or Nancy cartoons, it is suggested that you put this book down now” (9). In the same book, he offers some never-before-seen drawings from his “kindergarten days”, complete with the view from his barred bedroom window, a ‘family dinner’, with him under the table with the dog, him tied to a tree playing ‘games’ with his older brother, his father using him to play fetch with the dog, his father dangling him over the alligator exhibit at the zoo for the ‘amusement’ of other kids, and finally, a young Gary in the trunk of the car during the family’s annual vacation. These priceless drawings are the true beginning of The Far Side, as his later works in his adult years share much of the same energy and pomp as these kindergarten sketches (13-24).

While Gary certainly has his critics, he makes sure to let readers in on it. In one hilarious chapter in the same Far Side edition, Part 4: ‘Stimulus-Response’, Gary displays some of his best controversial cartoons and the scathing “hate” mail many of them received and the end result is, well, let’s just get into it. Gary believes that cartoons have a strange type of humor that can often get lost in translation (or interpretation). Cartoon humor is also unique in that it’s a totally silent world and creation and reaction. It is, as Gary puts it, a “daily shoot-in-the-dark approach to humor” (155). The target is obviously people who share similar senses of humor, however, that is not always the case, especially seeing how The Far Side was published right next to the Nancy cartoons, and Nancy readers were often the unwitting and ‘innocent’ bystanders knocked off their feet by those very cartoons. In one such, Gary attempted to capture a car-chasing-inclined dog’s ultimate fantasy of making the “kill” (of a car) and depicted a dog dreaming of themselves mounted atop their freshly-killed prey (in this case, a car), howling into the moonlight in triumph. The panel was captioned “When car chasers dream”. Sounds innocent enough, right? Well, Gary decided that since the car was supposedly “dead”, he ought to put it on its back (a universal “death” symbol). And since the underside of the car was now visible, being the perfectionist he is, he went and drew in the transmission case for a “touch of realism” (162). Most unfortunately, the location of the transmission and the place where he wanted the dog straddling the car conflicted and the ensuing panel (which neither Gary nor his editors noticed) seems to show the dog and the car being “romantically” entangled. The enraged letters and hate mail the paper received after this was colossal, with constituents writing that they were “disgusted” and offended by the “sick” cartoon, saying it belonged in Playboy, that Gary owed his readers an apology, and declaring they were immediately cancelling their subscription to save their young children’s minds from The Far Side’s “poor taste” (163).

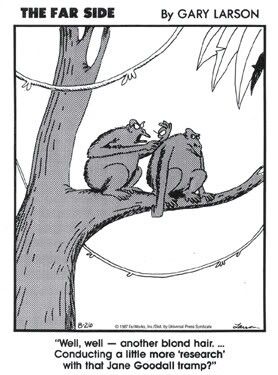

One of the most controversial Gary Larson cartoons, and perhaps one of the most iconic, is one that references the great Jane Goodall (who Gary himself is a big fan of). In the panel, one chimpanzee is grooming her mate and, plucking a hair from his back, says, “Well, well- another blond hair… Conducting a little more ‘research’ with that Jane Goodall tramp?” A few days after it was published, Gary’s syndicate received an incensed letter from a representative of the Jane Goodall Institute, livid that Gary would refer to Dr. Goodall as a ‘tramp’- “even by a self-described ‘loony’ as Larson.” The letter even implied litigation in the future from this cartoon. Naturally, Gary was horrified but before he could write an apology letter, he received the news that Jane Goodall herself loved the cartoon, and that she had no idea about all the madness going on over it. After a few phone calls, the cartoon was reprinted in not just the centennial issue of National Geographic, but was also used on a t-shirt as a fundraiser for her Institute (167). Though Gary has many more stories and explanations behind his more contentious cartoons, he always takes the criticism in stride and good humor, and never lets it squelch his artistic, and slightly macabre, creative spirit.

Another notable aspect of Gary’s work and something that always drew me to him was that he produced some quite provocative commentary on humankind and our overall overestimation of our species (Stein/Seattle). His ensemble cast of characters, usually comprising of mad scientists, aliens, cows (his favorite animal to draw, and according to him, “the quintessentially absurd animal for situations even more absurd.”) and the like, always contributed to a point in his comics and to the punchline (156). It was always very important to Gary to humble the great Homo Sapien species, reminding us that we are just that- another species. One such cartoon depicts a rabbit wearing a human’s foot around their neck for ‘good luck’ (The Mag). Another special addition in the 10th Anniversary edition of The Far Side includes a short story called “Zoology”, which goes as follows: “The bear and Carl lived together in the cave for several years until, one day, the true savagery of Nature being unleashed, Carl killed and ate him” (117). I mean, how much more direct can you get? It is quite ingenious.

Gary also uses this direct style of storytelling to commentate on animals, in both their pure innocence and their place amongst humans, or more correctly, the place in which we put them. He has several panels featuring domesticated, non-anthropomorphic dogs, one in which the End of the World is happening, complete with a giant mushroom cloud in the sky, buildings on fire, and a mass frenzy of panicked people flooding the streets and in the middle of it all, a dog, spotting another dog across the street and wagging its tail furiously. Gary writes in his (literal) commentary on the panel that he was attempting to focus on dogs’ childlike fascination with one another and that while our own world is coming to an end, is not necessarily the dog’s and that they are simply more excited about seeing another dog (a new friend!). Another dog panel features a group of Vikings returning to their boat after pillaging a kingdom that is burning in the background, and a dog, leashed to the bow of the boat, wagging its tail in anticipation of its master returning home. Gary says that this was meant to suggest that it doesn’t matter what you do for a living or “how big of a jerk you are”, your dog still likes to see you come home (138).

In yet another animal panel, this time featuring two tethered oxen pulling their master’s pre-industrial-America covered wagon in the middle of a desert, offers a more bleak perspective of animals, with the two oxen looking over at a fellow ox’s skull lying in the sand while their master looks forward, disconcerted. Here Gary plainly says that we all “look a little longer and harder at the things that fall upon our particular interests” (145). In this single, wordless panel, he opens up a pathway to a deeper conversation on not only the treatment of animals but also the human fascination with ourselves and our own lives, a contrast to the dog’s fascination and adoration for the other beings in the world. While I hate to be the one to open up a cynical dialogue on the faults of humanity, it was very difficult for me to not start to think. Just as humans, as the apex predators in this world, enjoy a cozy spot at the top of the food chain, so do the most privileged among us (generally white, upper-class, heterosexual, and male) occupy the spot at the top of the human chain and more often enjoy the luxeries that come with being the ‘apex predators’.

I never thought that a simple, wordless comic panel could conjure up such deep thoughts and carry such a strong visual and I certainly never thought, after picking up my first Gary Larson collection all those years ago, that these goofy, often-cow-themed cartoons could be something that I could actually analyze from a sociological perspective in college. Through this keen, woke, and wonderfully morbid sense of humor, Gary is able to provide this kind of commentary on the lives of his fellow homo sapiens and how we fit in this world, and the ways in which we are privileged to even get to decide.

*I refer to Gary Larson as “Gary” throughout this essay and, though I know it is ‘proper’ form to refer to him as “Larson”, I thought that this might make Gary uncomfortable and felt he would prefer to be called “Gary”. It also just seems more on par with what I know about him and his standards of professionality.

References

California Academy of Sciences – Academy Tour – Natural History Museum, https://web.archive.org/web/20140312211958/http://www.calacademy.org/exhibits/academy_tour/naturalhistory/farside.html.

Chris-Sims. “The Strange Legacy of Gary Larson’s ‘The Far Side’.” ComicsAlliance, 14 Aug. 2015, https://comicsalliance.com/tribute-gary-larson-far-side/.

Larson, Gary. The PreHistory of the Far Side: a 10th Anniversary Exhibit. Andrews and McMeel, 2006.

Mancini, Mark. “11 Twisted Facts About ‘The Far Side’.” Mental Floss, 28 Nov. 2016, https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/88286/11-twisted-facts-about-far-side.

“20/20.” 20/20, episode Gary Larson, ABC, 8 Jan. 1987.

Stein/Seattle, Joel. “Life Beyond.” Time, Time Inc., 29 Sept. 2003, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,490695,00.html.

The Mag. “50 Reasons to Subscribe to mental_floss (#45, Gary Larson).” Mental Floss, 12 Nov. 2007, https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/17358/50-reasons-subscribe-mentalfloss-45-gary-larson.Weise, Elizabeth. “Gary Larson Goes Wild.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 22 Nov. 2006, https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/life/2006-11-20-larson-cover-usat_x.htm.